Gavin Larkin was an advertising “creative” whose father, Barry, committed suicide nearly 20 years ago. He found himself trying to stop the pain of grief his family endured, and decided to do this by asking one question – “Are you OK?”.

In 2009, he established the R U OK? foundation to enable everyone, in all levels of society, to encourage and ask “Are you OK?”

Based on the work of Dr Thomas Joiner, who describes at risk people as having three dominant forces – a feeling of being a burden on others, a belief they can withstand a high degree of pain, and a disconnect from others.

Gavin used his advertising and marketing skills to establish R U OK? Day, an annual day give society permission to ask. He sadly passed away in 2011.

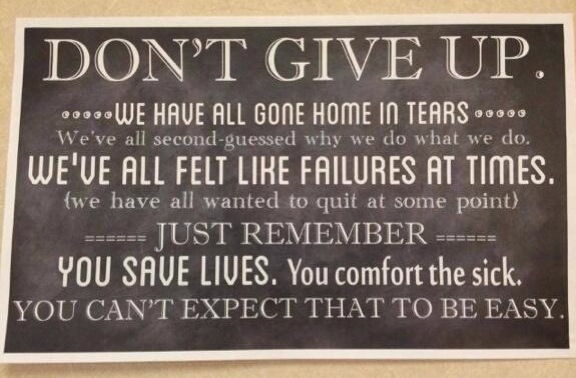

Sometimes we need reminding that health care workers are no different from the rest of society, and that in healthcare, Every Day is R U OK? Day…

Healthcare is hard

So here’s the thing. This is personal. Apart from many useful links, this post is almost entirely anecdotal. And my chest is a bit tight contemplating writing it – so I know it won’t be easy.

I work in a really supportive workplace, which is surprising for the number of staff. In fact, the whole hospital is like that. Nodding acquaintances, people you don’t know, but who you know you’ve seen and will undoubtably see again. You nod hello in the corridor or elevator.

Occasionally, we hear of a colleague from another department who has taken their own life. Usually it is someone you don’t know, like the nodding acquaintance, but someone you do know is connected to them in some way. We wonder what happened, how we could have helped…

In my workplace, we have a loose collection of nurses who take on the role of “Peer Supporter” (I am one – the little sticker on my ID badge identifying me as such is one of the qualification badges I am most proud of). We choose ourselves, or are identified as “the right kind of person” and asked to think about taking the role.

The right kind of person to be a peer supporter is approachable and discreet (when it counts) and has undertaken a short course covering how to encourage someone to obtain help, where to direct someone to help, self-care, and limits of expectations (you can’t save everyone yourself, don’t try).

As stated in the picture above, healthcare is hard. It asks a lot from us. We see things, we do things, we know things. We can’t un-know. And we cope. We have humour. We all know the jokes about going to dinner with a group of nurses (we are apparently the worst at this but I suspect there’s a bit going on in the other professions) and the conversation quickly turns to work. We sometimes find ourselves describing things at the dinner table in company with civilians and everyone goes silent at something we’ve said.

We normalise the abnormal, the difficult and the things that are unknown to everyone else.

Some of us found our way into the industry by accident, we didn’t know what else to do with ourselves, via a calling, family expectations, as many reasons as there are practitioners. But whatever the reason, we know if we wanted easy we would have done something else.

We feel we can deal with what our jobs ask of us. Any pain we experience isn’t the same as our patients’ pain, they’re the injured, the ill, we can give them medications, analgesic modalities from pills to subcut or IV boluses, to PCA’s to epidurals or local anaesthetic infusions, dissociative medications, we can use distractive therapies with them, validate their feelings, ventilate their emotions…

We can have a high degree of pain tolerance. But we might not be equipped to know we even have pain. Ours might not be physical pain but psychic pain. The pain of seeing the same physical pain every day. The pain of coping with what we do.

Then to complicate things, we have the disconnect from others. This can be can be any kind of disconnect. The obvious disconnect in healthcare is the shift work. We work different hours. We work with different people, each of us having our own schedule across the week.

The disconnect can be as a result of the knowledge that we are aware of things about life that others don’t know, and don’t really want to know, despite their curiosity at dinner parties.

Pain and the disconnect can be in any area of our lives and from any area of our lives. Look again at Dr Joiner’s risk factors for suicide. Pain and the disconnect. If we include a feeling of being a burden on others – I don’t want to bother my spouse, my family, my friends, my colleagues…my patient is the one with the problem, I’ll just carry on…

This is personal.

I was that person. I had a run of several difficult situations involving a particular type of patient at work. I had a very high tolerance for pain – I was as capable and as professional as I have ever been in my career. I was working my ICU job, I was working agency in anaesthetics, and I was working in tourism to relax.

Then, one day while completing my bed area checks in my role as an ACCESS nurse, a colleague asked me a surprising question.

“How are things? Are you OK?”

I surprised myself by telling her that I wasn’t. I really was not OK. I was in danger of becoming the one everyone wondered about. I had a plan, I had most of what I needed, I was consciously avoiding certain patients, I was socially isolated due to family dynamics, I was grieving for a family member who had died almost exactly a year earlier (and who was responsible for propelling me into nursing in the first place).

My colleague referred me to one of our Peer Supporters. I saw a work provided psychologist that afternoon. I took three weeks leave, I had six months away from my workplace, but was supported in another role in a different area on reduced hours.

I took up educating (one door closes, another opens). I worked university terms looking after students, and worked clinically back in my chosen area around the university year. When I went back to Intensive Care I undertook a performance appraisal from one of the ICU educators (at my own request) to help me with my confidence. I worked hard to get back to where I was, and I knew I was supported. I’m still trying to get that balance.

But I learned something…

After working 8 years as a theatre nurse, I knew my emotional resilience was good.

After working 4 years in ICU on top of that I knew my emotional resilience was very good.

After having looked after a disabled family member since I was 13 years old (the year I learned how to place NG tubes), with a hospital in the home situation (we had an oxygen concentrator, pulse oximeter, and suction, and my sister would occasionally require IV drug administration via a hickman catheter) I knew my emotional capacity was as good as anyone I worked with.

And still I needed help…

You never know. Until you ask.

R U OK?

If this blog has highlighted issues for you or someone you know please do not hesitate to obtain help. Or call Lifeline 13 11 14.

Do you or a loved one need help? Find help now.

R U OK? is a not-for-profit organisation dedicated to encouraging and empowering all people to ask “are you ok?” of anyone struggling with life. Our vision is a world where everyone is connected and is protected from suicide. This year, R U OK?Day is Thursday 11th September.

Find out more: ruokday.com